One hour west of Denver, the historic towns of Central City and Black Hawk still tell the story of Colorado’s roots.

The Central City Mining District kicked off Colorado’s first gold rush. John Gregory discovered gold nuggets and flakes in Clear Creek and the event brought nearly 100,000 gold-hungry prospectors across the barren plains and into the Rocky Mountains.

The district’s heyday lasted a half-century, boosted by ore processing techniques pioneered at the Black Hawk mills. Bigger booms later erupted at Leadville, Creede and Cripple Creek, but Central City came to be known as the Richest Square Mile on Earth.

This mill ruin in Gregory Gulch is one of several that still dot the area around Central City and Blackhawk.

Miners’ shacks tilted up the gulch, while merchants and mine owners built larger houses along Central City’s “Banker’s Row.” Mines operated day and night, as did the Black Hawk mills. Schools and churches went up to meet families’ needs.

Miners’ shacks tilted up the gulch, while merchants and mine owners built larger houses along Central City’s “Banker’s Row.” Mines operated day and night, as did the Black Hawk mills. Schools and churches went up to meet families’ needs.

The two cities enjoyed a fierce rivalry. Central City claimed the wealthier citizens and most important businesses and civic institutions. One mile down the gulch, Black Hawk flourished as a nitty-gritty industrial town, home to European immigrants who came to labor in the mills and work underground in the mines. Both towns boasted numerous illustrious pioneers, who moved here during territorial days and became political and industrial leaders ensconced in palatial homes on Capitol Hill.

The mines eventually yielded more than $200 million in mineral wealth, but the great boom had busted by the 1920s. People departed the district in droves, leaving behind vacant houses and business buildings.

The “ghost town” appearance exuded a certain charm and soon tourists and artists crept up the canyon highway to take in the bewitching mining ruins and the picturesque properties. Denver artist Vance Kirkland, Boulder professor-author-artist Muriel Sibell Wolle and others captured the dramatic quality of the places.

In the 1930s, Ida McFarlane and others associated with Denver University purchased the crumbling Central City Opera House and restored it to its original glory. Each summer the “ghost town” sprang to life, peopled by performers, production staff and music lovers.

Interest in the area increased after World War II as Central City and Black Hawk attracted visitors seeking the “real Colorado” experience. Saloons featured ragtime music and cheap beer. Gift shops and ice cream parlors opened. Several mines offered underground tours. The Central City Jazz Festival became a summer tradition, as did rollicking Lou Bunch Days featuring “bed races” with “prostitutes” rolling down Main Street.

Myth, legend and lore unfolded, popularized by Colorado’s most colorful historian, Caroline Bancroft, and with Douglas Moore’s “The Ballad of Baby Doe,” which debuted at the Central City Opera in 1956.

The Gilpin County towns again made history in 1990 when they banded together with Cripple Creek and asked Colorado voters to approve a constitutional amendment to allow gambling as an economic generator. A bonanza rivaling the first gold rush unfolded — with sky-rocketing land prices and investors rushing in. Las Vegas-sized casinos went up in the gulch, but many casinos boomed and busted.

Despite the casino building boom, the two towns retain a historic look and feel and boast numerous architectural treasures. Touring the gulch takes you back to where it all started, when Colorado was in its infancy and gold was king. Black Hawk still contains two of the state’s oldest public buildings — the 1863 Presbyterian Church and the 1870 Black Hawk Schoolhouse perched on the cliff side north of downtown. Several 1870s commercial buildings were rescued from decay and converted into casinos.

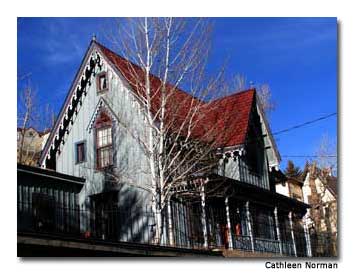

Meanwhile, casinos with massive modern fronts dominate the banks of Clear Creek where clanging, clattering, smoking ore mills once operated. The Lace House stands solitary on the hillside. The local historical society saved the beloved architectural gem from rack and ruin in the 1980s and the tiny treasure will soon be moved to a historic building park at the west edge of Black Hawk.

Central City offers some of Colorado’s oldest architecture. Quickly rebuilt after destruction by fire in 1874, the Main Street is lined with two- and three-story buildings of brick and stone. Groceries, bakeries, dry good stores and saloons operated at the street level, while lawyers officed, physicians practiced and innkeepers ran hotels in the second stories.

West and north of downtown stand the civic institutions — including the County Courthouse, Central City School (now a wonderful museum), St. James Methodist Church and Central City Opera House. On the hillside above are the larger dwellings of merchants, mine managers and lawyers.

Casey Street crawls up the hillside and meanders along a ridge below Central City. Named for an illiterate Irish miner who gained great wealth overnight, it became a popular neighborhood. “Walking the Casey” became a summer-evening pastime, especially for courting couples.

One mile southwest of Central City you can visit Nevadaville, once a bustling city of several thousand miners, now the home to a handful of residents. One mile northwest of Central City you can visit the graves of many of the district’s original inhabitants in the cluster of six cemeteries.