Sunset casts its golden light and eerie shadows across the vast sand dunes. We have just arrived, and feel like we should kick off our hiking boots and dig our toes into the silky sand. But no, it’s only about 40 degrees now, and it will get lots colder once the sun dips behind the San Juan Mountains. I shoot a few photos before dusk settles, then leave for our motel in Alamosa, anxious to return in the morning to hike and explore.

Sunset casts its golden light and eerie shadows across the vast sand dunes. We have just arrived, and feel like we should kick off our hiking boots and dig our toes into the silky sand. But no, it’s only about 40 degrees now, and it will get lots colder once the sun dips behind the San Juan Mountains. I shoot a few photos before dusk settles, then leave for our motel in Alamosa, anxious to return in the morning to hike and explore.

A weekend visit to Great Sand Dunes National Park & Preserve (recently upgraded from a national monument) reminds us why this place is so special.

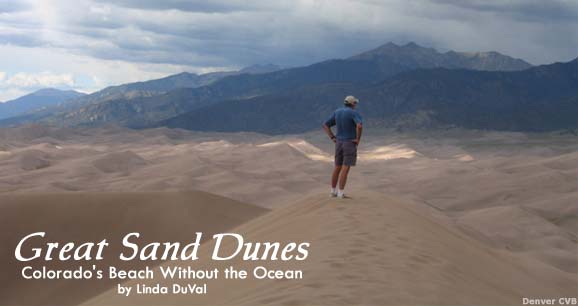

These are the tallest dunes in North America, topping out at over 750 feet. The dune field itself lies in Colorado’s San Luis Valley, flanked by the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the east, with the San Juans in the distance to the west. There is no ocean. These dunes are a unique geological feature, surrounded as they are by the Colorado Rockies.

“I call it Colorado’s beach,” says park ranger Libbie Landreth, who has been here since 1981 — most of her career.

While the obvious attraction is the dunes themselves, Landreth encourages visitors to explore other aspects of the park, such as the two water courses (Medano and Mosca creeks), the mountainous wildlife preserve and the sand flats.

Visitors can hike the dunes (not easy, and made more difficult by the park’s 8,200-foot altitude), or other trails along the edge of the dunes and up into the preserve, which ascends to the ridge line north of the park.

Our first hike of the day, into the dunes themselves, has us trudging, our boots sinking into the soft sand, as we make slow progress up the first row of dunes. Even though my husband and I both work out, the climb leaves us breathless and a little discouraged. (You know that dream about running in sand and not getting anywhere? Well, this is the reality.)

From here, we watch other hikers walking dogs, shooting photos, or playing in the sand.

On this sunny but cool autumn Sunday, a group of students from nearby Adams State College in Alamosa try their luck with “sledding’’ down the slopes. They take a run, drop belly first on the mats — and stick. The rubber mats won’t slide, and they roll around laughing at their folly.

Across the sandy valley on another dune, a family has better luck with a hard plastic saucer-sled. But the climb back up is akin to walking up a ski slope to get a few seconds of thrills.

Skiers and snowboarders also try their luck here, with some success, says park ranger Patrick Myers. They have the best luck right after a rain or snowfall, he adds.

“It’s allowed, but not necessarily encouraged,” he says. It’s not that it does much damage to the park, “which is constantly shifting and changing anyway,” it’s just more disruptive than the usual park activity. “As long as they stay off the vegetation, it’s OK,” he says.

But there’s more to the park than just the dunes.

Visitors can explore a number of life zones in a relatively small area — from the wetlands and riparian habitat surrounding the creeks to the alpine tundra at the top of the nearby 13,000-foot peaks.

The dunes themselves encompass over 30 square miles — about the same size as the city of Pueblo in southern Colorado, Myers says. Add to that the preserve and other adjacent land purchased to complete the park, and you have a total of about 234 square miles full of mule deer, pronghorns, elk, bighorns, mountain lions, bears, coyotes, raccoons, marmots, rabbits, pikas, kangaroo rats and several odd species of insects. A captive bison herd roams the nearby plains.

On our second hike of the day, up the four-wheel-drive Medano Pass Road to a spot dubbed Point of No Return, we encounter mule deer, easier (and lots firmer) hiking trails, and a class from the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs getting a lesson in the local fauna — in this case, a giant Ponderosa pine tree.

The dunes are accessible all the time, year round. The new $4.5 million visitor’s center is open daily. Check out the exhibits, displays and the film if you have time. Plenty of campsites in the treed area near the dunes accommodate those who want to spend a night, or more.

The park itself never closes. But visitors are warned to stay out of the dune field on hot summer afternoons; the surface temperature of the sand can get anywhere from 140 to 150 degrees on hot, sunny days. By contrast, the snow often melts off within a few hours after a winter storm, making the dunes a pleasant hike on a winter’s day.

Another unusual aspect of the park is the wavelike action found in Medano Creek each spring. The water flows in pulses, not a steady stream, and is so shallow anyone can wade — most of the time.

“Some years, the water is high enough (a foot or more deep) for kids to body surf on the waves or pulses,” Landreth says. “When the water gets that high, parents need to watch small children. I haven’t seen it that high, though, since the 1980s.”

And don’t forget it will be cold, she says. “After all, it is snowmelt.”

Medano Creek flows best during spring thaw, from April until early June. That’s when water birds make their annual appearance. Unfortunately, that’s also the season for flying insects.

“I can handle the mosquitoes and no-see-ums, but those pinon flies will fly right in your mouth and nose,” Landreth says. Good insect repellent is suggested at that time of year.

From experience, I can add that the no-see-um bites can be insidious, seeming like nothing to start, then itching like mad for weeks.

How the dunes were formed here seems a mystery, but not to anyone who’s ever experienced the fierce winds that can sweep across the San Luis Valley. Sand blows straight sideways, with the prevailing wind coming from the southwest.

Gradually, the dunes could have been formed as recently as 12,000 years ago. Despite their stability, the dunes seem ephemeral, always shifting. Always fascinating and eternally mysterious. And that’s part of the draw.

“People come to Colorado expecting to see mountains,” Landreth says. “This is just so unexpected.”

If You Go

Great Sand Dunes National Park & Preserve is 35 miles northeast of Alamosa, in the San Luis Valley of south central Colorado. It’s about a four-hour drive from Denver.

Admission: $3 per person. Entrance fee is valid for one week.

Activities: Hiking and playing in the sand dunes are the most popular activities. Horseback riding and mountain biking are now allowed in the dunes, but they are on designated trails in the park. Motorbikes and ATVs are not allowed in the park.

Lodging: There are plenty of campsites in the park (call for reservations) and there’s a lodge just outside the park entrance. Many visitors stay in nearby Alamosa, which has a range of chain motels and local bed-and-breakfast inns.

Information: Contact the park, 719-378-6300, or www.nps.gov/grsa.

For information on visiting the Alamosa area, call 800-BLU-SKYS, Ext. 932, or go to the Web site, www.alamosa.org.

Linda DuVal, former travel editor of the Colorado Springs Gazette, is a freelance writer living in Colorado Springs.

From the Editors: We spent a heap of time making sure this story was accurate when it was published, but of course, things can change. Please confirm the details before setting out in our great Centennial State.